Development report 2024

Related Files:

Development Report 2024

In Slovenia, a robust post-COVID-19 economic recovery, supported by improved conditions in trading partners and substantial fiscal policy measures, was followed by a slowdown in economic growth and an increase in inflation in 2022 and 2023 in the context of the energy crisis. The impact of rising cost pressures on competitiveness and the population's lower purchasing power was cushioned by measures to support businesses and the population. Despite a relatively weak performance in 2022, economic growth surpassed the EU average again last year, with GDP per capita in purchasing power parity reaching 91% of the EU average in 2023. However, the pace of narrowing the gap with the EU average has slowed: while the gap decreased by 6 p.p. from 2016 to 2019, it only declined by 2 p.p. from 2020 to 2023. Due to the epidemic, the general government balance turned from a surplus to a large deficit in 2020. The deficit gradually decreased with the phasing-out of the temporary COVID-19 support measures for businesses and the population. In 2023, however, it was still significantly affected (-2.5% of GDP) by measures aimed at mitigating the energy crisis and addressing the consequences of floods. Given the new fiscal rules, sustainable deficit reduction will require prioritised planning. Human resource development for delivering quality public services and facilitating the green and smart transformation is progressing too slowly and, despite severe labour shortages, access to quality jobs remains a challenge for certain population groups. While the quality of life has gradually improved, the at-risk-of poverty rate and inequalities have slightly increased in 2022 and 2023. Additionally, the accessibility of public health and long-term care systems faces growing challenges. A review of past trends and development challenges, as outlined in this year's Development Report, shows, similar to previous years, that the key areas of development policy requiring prioritization within the framework of public finances are: accelerating productivity growth and the transition to a low-carbon circular economy, reforming social protection systems (healthcare and pensions), and enhancing the strategic governance of public institutions. In view of the scarcity of public funds, the realisation of objectives in a number of areas will have to be combined with the use of private funds.

Related Files:

The priority areas for action analysed in this year’s report, which we consider crucial for the long-term sustainable development of Slovenia and higher quality of life, relate to the following challenges:

Trend productivity growth remains weak, although some of its factors have been gradually improving for some years. However, to achieve a significant boost in productivity, it is imperative to accelerate investment in smart and green transitions, as well as to expand and deepen business transformation processes within companies.

The educational attainment of the population has been on the rise for several years; however, the pace of human resource development to ensure the provision of quality public services and to facilitate the green and smart transformation of the economy has been too slow; certain indicators of the quality of basic and upper secondary education have shown signs of deterioration in recent years.

While the health status of the population has nearly returned to pre-epidemic levels over the last two years, the accessibility of public health and long-term care systems faces growing challenges.

Despite a severe labour shortage due to demographic change and employment rates at an all-time high, access to quality jobs is still a challenge for some people.

The at-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) rate and income inequality, which are among the lowest in the EU, have risen slightly in the last two years. However, the at-risk-of poverty rate for some vulnerable groups has consistently exceeded the EU average for many years.

Given the lack of progress in the transport sector and in the use of renewable energy sources, the pace of the transition to a low-carbon economy is too slow and the circular material use rate as a measure of the circular economy remains relatively low.

Certain aspects of government efficiency have shown improvement in recent years (digitalisation and introduction of quality standards in public administration, improvement of the quality and efficiency of the judicial system, reduction of administrative barriers, modernisation of public procurement practices), although most of the key challenges identified in recent years are still relevant today (lack of effective public sector governance, high burden of state regulation, mistrust in the rule of law and the judiciary, high perception of corruption, lack of predictability of the business environment and legislation); the good results in the areas of safety and global responsibility persist.

Indicators of Slovenia's development:

- A highly productive economy creating value added for all

- Lifelong learning

- An inclusive, healthy, safe and responsible society

- A preserved healthy natural environment

- A high level of cooperation, training and effective governance

1. Gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power standards

In 2023, Slovenia reached 91% of the EU average in terms of economic development, measured in GDP per capita in PPS (34,400 PPS), which is 1 p.p. more than in 2022 and the same as the 2008 peak. A decomposition of GDP per capita into productivity and employment rate shows that the gap in economic development with the EU average is now entirely the result of the relatively lower level of productivity, which, however, reached 85% of the EU average in 2023, the highest level ever achieved. The employment rate in Slovenia was above the EU average throughout the period analysed – by 7% in 2019–2021 and by 8% in 2022 and 2023.

Slovenia’s position relative to the average level of development in the EU was only 2 p.p. higher in 2023 than in 2005, while the majority of the new EU Member States have made considerable progress in this period. Compared to 2005, 14 Member States have improved their position relative to the EU average, led by Ireland (by 61 p.p.), while of the new Member States, all except Cyprus have improved their position. Thirteen Member States moved further away from the EU average during this period, most notably Greece (by 28 p.p.), Luxembourg (by 16 p.p.) and Italy (by 15 p.p.). From 2015 to 2019, Slovenia moved closer to the EU average (by 6 p.p.), but from the COVID-19 outbreak (in 2020) to 2023, Slovenia’s progress was very modest (only 2 p.p.). In the period 2015–2023, the greatest progress was made by Ireland (31 p.p.), Romania (21 p.p.), Bulgaria (16 p.p.) and Croatia (15 p.p.), while the largest deterioration occurred in Luxembourg (42 p.p.), Sweden (11 p.p.), Germany (9 p.p.) and Austria (8 p.p.). Luxembourg and Ireland were most significantly above the EU average in 2023 (by 140% and 112% respectively). The spread in the GDP per capita indicator in PPS between the EU Member States, which in 2000 was at 1:9.3 (Romania/Luxembourg), has been narrowing over the years, falling to 1:3.7 in 2023 (Bulgaria/Luxembourg).

2. Real GDP growth

The strong post-COVID-19 economic recovery was followed by a slowdown in economic growth in 2022 and 2023 in the context of the energy crisis. After the recession during the global financial crisis, economic growth largely accelerated in 2014−2017, but it then slowed in 2018 and 2019, mainly due to a slowdown in foreign demand and uncertainty regarding international trade and geopolitical relations. In 2020, all GDP components, with the exception of government consumption, declined due to the epidemic and the related restrictions. With a strong upswing, economic activity in 2021 exceeded the pre-epidemic level. This was mainly due to private consumption, which was supported by government measures and a significant drop in the savings rate. In 2022, growth in the first half of the year stemmed mainly from the post-COVID-19 recovery, while the cooling of activity in the international economic environment due to the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis, together with the inflationary impact on purchasing power, contributed to a significant cooling of activity by the end of the year. Amid high employment, private consumption growth remained relatively strong. Growth in investment and construction activity was supported by public investment, which was also stimulated by EU funds. In 2023, economic growth weakened further, particularly in the export-oriented part of the economy due to the economic slowdown in Slovenia’s main trading partners and a deterioration in cost and price competitiveness (see Section 1.2.1). Growth in private consumption also slowed, mainly due to the impact of inflation on household purchasing power. On the other hand, investment growth and construction activity remained strong.

After several years of relatively high growth, the decline in real GDP in 2020 was lower than the EU average and the recovery in 2021–2023 was stronger on average. The only year with lower growth in the last three years was 2022, this mainly due to the above-average decline in manufacturing production in the context of the energy crisis. The higher growth in 2023 (SI: 1.6%, EU: 0.4%) was a consequence of faster growth in almost all components of domestic consumption. The growth of economic activity in Slovenia was mostly lower than the (unweighted) average of the other new EU Member States before the pandemic year 2020 and mostly higher afterwards.

3. General government debt

Amid high nominal GDP growth, general government debt fell to 69.2% of GDP in 2023. In 2020, it rose by 14.2 p.p. to 79.6% of GDP due to the stimulus measures taken to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 and the economic downturn. With the strong economic recovery and the reduction in the country’s cash reserves, it fell by 5.2 p.p. in 2021, followed by a slightly smaller decline in 2022 (by 1.9 p.p.). In 2023, the general government debt-to-GDP ratio further fell by 3.3 p.p. to 69.2%. The debt ratio fell due to the impact of nominal GDP growth and also the lower primary deficit. Interest expenditure increased slightly in 2023 (to 1.2% of GDP) due to rising government bond yields but was still well below the 2014–2015 peak (3.2% of GDP) and the 2019 level (1.7% of GDP). In the period 2019–2023, during which the countries were exposed to numerous economic shocks, the increase in public debt in Slovenia was among the lowest (3.8 p.p.) in the EU and was below the average for euro area countries (6.3 p.p.) and the EU as a whole (5.4 p.p.), while some countries managed to reduce their debt.

4. Fiscal balance

The general government deficit continued to decline in 2023 and amounted to 2.5% of GDP. The improvement in the government’s fiscal position in 2015–2019 was interrupted by the exceptional circumstances related to COVID-19, which led to a sharp deterioration in 2020 (deficit of 7.6% of GDP). With the post-COVID-19 recovery and lower expenditure on measures to mitigate the consequences of the epidemic, the deficit fell to 3% of GDP by 2022 and further declined to 2.5% of GDP in 2023. Revenue growth rose to 10.6% last year (from 7.4% in 2022), driven by all main revenue groups: taxes, social contributions, revenue from state property and EU sources. Expenditure growth in 2023 was slightly lower than revenue growth (9.5%) but has accelerated significantly compared to the previous year (4%). This was mainly due to an increase in expenditure on subsidies to companies (due to rising energy prices and floods) and wage increases in the public sector, after expenditure on these two categories had been reduced in the previous year due to the discontinuation of measures to mitigate the consequences of the epidemic. Growth in general government investment was also high last year (9.3%) (end of the 2014–2020 financial perspective, including REACT-EU, Recovery and Resilience Facility funds, post-flood reconstruction), but lower than in 2021–2022, the period of post-COVID-19 recovery, when it was around 26%. Growth in expenditure on social benefits and transfers was also lower than in 2022.

In its autumn forecast, the EC estimates that the deficit in the euro area fell from 3.6% of GDP in 2022 to 3.2% in 2023. These projections show that the deficit has remained above the reference value of 3% of GDP in a number of countries due to a significant slowdown in economic growth and measures to support the economy and population in the face of high energy and food prices. The impact of these measures, which include tax cuts, transfers to individuals, subsidies for energy and production, price caps on energy markets, and windfall taxes, on the general government deficit is estimated by the EC (2023a) at 1.2% of GDP in both the EU-27 (1.4% of GDP in 2022) and Slovenia (1.2% of GDP in 2023 and 1.1% in 2022). According to the EC estimate, the fiscal policy stance in the euro area was quite heterogeneous last year and restrictive on average (as in Slovenia).

5. Current account of the balance of payments and net international investment position

After one year of deficit, the current account showed a large surplus again in 2023 (EUR 2.8 billion or 4.5% of GDP). In 2020, when the epidemic severely curtailed domestic spending, the current account surplus rose to its highest level ever (7.2% of GDP). The faster recovery of domestic demand compared to external demand and the deterioration in the terms of trade amid sharp fluctuations in commodity prices on the world markets led to a significant decline in the current account surplus in 2021, before turning to a deficit in 2022. The return to a surplus in 2023 was mainly due to the goods trade balance, as real goods imports fell even more sharply than exports. The sharp decline in imports was mainly caused by a fall in inventories and lower household consumption. In addition to the quantity fluctuations, which contributed EUR 1.5 billion to the annual change in the trade balance (EUR 2.6 billion), the improved terms of trade also had an impact of EUR 1.1 billion. The growth of the services surplus continued, especially in trade in transport and construction services.

Slovenia’s international investment position further improved in 2023 and was positive for the first time since 2002. Compared to 2022, total claims in relation to GDP increased, while total liabilities remained largely unchanged. The net outflows of the Bank of Slovenia (BoS) and the private sector were higher than the net inflow of government financial assets. The BoS increased its foreign liabilities and even more its currency and deposits in the framework of the TARGET settlement system, mainly in connection with the placement of money by domestic commercial banks abroad and the issuance of securities in Slovenia. In 2023, the general government sector increased its net foreign liabilities. The country has increased its debt to foreign portfolio investors and foreign lenders. Higher short-term interest rates on the international money markets have led to an increase in claims in the segment of financial derivatives. The private sector has increased its net external claims. Non-financial companies, domestic commercial banks and investment funds increased their investments in foreign equity and debt securities. Households increased their deposits in foreign accounts in view of rising interest rates and thus higher yields, while other financial intermediaries increased their debts to foreign lenders. Inward FDI flows have risen in recent years, on account of the sale of ownership stakes in domestic companies and recapitalisation, and exceeded the outward FDI flows.

6. Financial stability

The financial system has remained stable in recent times amid a slowdown in economic activity. The share of non-performing loans has fallen significantly in recent years and, according to the EBA, was even slightly below the euro area average in the third quarter of 2023. Data from the Bank of Slovenia show that the weather disaster in August had no negative impact on the non-performing loans ratio. Only in the sectors that were hit hardest by the epidemic (e.g. accommodation and food service activities) is the ratio still relatively high, but here too it has already fallen significantly. The ECB continued to normalise its monetary policy throughout 2023, while at the end of the year, as inflationary pressure eased, it stopped raising its key interest rates. In 2023, they rose by 200 basis points and reached a level comparable to 2008. As a result, credit conditions for companies, households and governments in Slovenia and elsewhere in the EU deteriorated. Although yields to maturity of government bonds and lending rates for companies fell slightly at the end of 2023, they were above the average for the EU and the euro area.

The banks maintained a high level of capital adequacy and liquidity in 2023. The capital adequacy of the banking system continued to improve with a reduction in risk-adjusted assets (sale of a leasing company, lower exposures to the state and slowdown in lending activity) and an increase in capital through retained earnings and was relatively high given the minimum capital requirements. Liquidity also increased and was among the highest in the euro area. This is indicative of the high capacity to cover net liquidity outflows over a short-term stress period (BoS, 2023a). Although the inflow of deposits from the domestic non-banking sectors at banks fell significantly in 2023 (by more than 60%, to EUR 1 billion after high inflows in 2020–2022), this does not mean that there is a need for other sources of funding, as the slowdown in the lending activity of banks was even more significant. The share of foreign sources of funding increased slightly but was still relatively low. In the second half of 2023, when deposit interest rates rose, the maturity structure of deposits in the non-banking sector also improved slightly. Overnight deposits still dominate the deposits structure (80%), but their share fell by about 5 p.p. compared to 2022.

7. Financial system development

Slovenia’s gap with the EU in the level of financial system development remains wide. In 2023, the banking system’s total assets increased by 5.1% despite the decline in lending activity, while the indicator of total assets as a share of GDP further decreased slightly amid higher nominal GDP growth and reached about 30% of the EU average. On the investment side, the growth in the balance sheet total was primarily due to an increase of funds in central bank accounts, while the volume of debt securities of foreign financial institutions also increased. Looking at the sources of finance, the increase was mainly due to time deposits from domestic non-banking sectors and debt securities issued. Amid good business performance, the banks built up additional capital and reserves. The decline in the loan-to-deposit ratio, which was interrupted in 2022, continued in 2023 and reached 0.67, less than half of the 2008 peak. The gap with the EU average in terms of capital market development, measured by the stock market capitalisation-to-GDP ratio, narrowed slightly in 2023, but it was still only around one-fifth of the EU average. The market capitalisation of shares listed on the Ljubljana Stock Exchange increased by almost one-fifth in 2023, against a background of positive capital market developments. A large part of the Slovenian capital market is represented by government bonds, while corporate financing via issuance of shares and bonds is still negligible compared to other sources of financing, and the volume of trading in issued securities is low, which does not attract new investors.

The development gap with the EU average in the insurance sector further narrowed in 2022 and remained smaller than in other segments of the financial system. The volume of insurance premiums in relation to GDP was over 70% of the EU average. Premiums increased by 7% in Slovenia, while they stagnated in the EU. At 8.5% (EU: 5%), growth in non-life insurance premiums matched the highest level in ten years, while life insurance premiums rose by 3.5% after two years of decline, compared with a fall of almost 5% in the EU. The gap in the life insurance sector has therefore narrowed, but Slovenia is still below two-fifths of the EU average. Interest rates on deposits rose slightly last year but were still below the euro area average. The large volume of household deposits in banks, which continues to grow, and low deposit interest rates and the supply of government securities for non-professional investors could accelerate a shift in household saving habits towards an increase in retirement savings, which could increase the share of life insurance and capital market investments in the future.

8. Regional variation in GDP per capita

Amid a slowdown in economic growth in most regions, the gap in GDP per capita between the Osrednjeslovenska and other regions narrowed in 2022. Real GDP decline in all regions in the first year of the epidemic and the acceleration of growth in 2021 was followed by mostly modest economic growth in 2022. The Obalno-Kraška region, which has a high share of accommodation and food service and tourism activities in the structure of its economy and was most affected by the COVID-19 epidemic, recorded the highest economic growth (9.7% in real terms) among all regions in 2022. This led to the narrowing of the gap in GDP per capita and brought the region close to the national average, although it was still below the pre-COVID-19 level. The Gorenjska region, the only other region with higher GDP growth than in the previous year, also recorded high economic growth. In the Jugovzhodna Slovenija region, real GDP fell, most significantly in the Posavska region (-6%), widening the gap to the Slovenian average. In the Osrednjeslovenska region, which stood out for its particularly high economic growth in 2021, GDP only grew by 1.7% in real terms (SI: by 2.5%), which is also the main reason for the narrowing of the gap between Osrednjeslovenska and the other regions.

The relative dispersion of regional GDP per capita also points to a reduction in regional disparities in 2022. At 24.1%, it was 0.7 p.p. lower than in the previous year, but it did not yet reach the pre-epidemic level. The ratio between the two extreme statistical regions decreased slightly (1:2.7), due to lower growth in GDP per capita in the Osrednjeslovenska region and higher growth in the Zasavska region. The gap has also narrowed within the Zahodna Slovenija cohesion region.

Statistical regions, with the exception of the Osrednjeslovenska region, lag behind the European average in GDP per capita and also some neighbouring regions in other countries. In 2022, of Slovenia’s statistical regions, only the Osrednjeslovenska region exceeded the European average (by 31 index points), while the Posavska region again widened the gap to the European average the most. The Zahodna Slovenija cohesion region was above the European average by 9 index points, while the Vzhodna Slovenija cohesion region remained one of the least developed regions, with 73 index points of the European average. The Obalno-Kraška region narrowed the gap to the European average the most (by 6 index points). Given the considerable lagging behind of the majority of the regions, the catching up with the European average seems to be an extremely complex long-term objective. Therefore we compared individual statistical regions with neighbouring regions in other countries that are at a similar stage of development. In 2021, the Osrednjeslovenska region performed 3 index points better in terms of GDP per capita than the Klagenfurt–Villach region, while the Goriška region lagged behind the Italian Gorizia region by 9 p.p. and the Pomurska region was at the same level as the Hungarian Vas region and was ahead of the Hungarian Zala region by 7 p.p.

9. Productivity

The gradual narrowing of the productivity gap between Slovenia and the EU average continued during the epidemic and the energy crisis. Slovenia reached 85% of the EU average productivity level (in purchasing power standards) in 2023, which is 2 p.p. more than in 2019. Amid a sharp deterioration during the global financial crisis and a gradual catch-up after the crisis, this was 1 p.p. above the 2008 peak and still far from the SDS 2030 target (95% of the EU average).

During the energy crisis, real productivity decreased most notably in export-oriented activities. In 2023, with the cyclical slowdown in GDP growth and further employment growth, overall economic productivity, measured in terms of real GDP per employee, remained at a similar level as before the energy crisis (a decline of 0.4% in 2022 and an increase of 0.4% in 2023). Under the influence of weaker foreign demand and unfavourable conditions on the energy markets, (energy-intensive) industry and the transport and trade sectors made a negative contribution to productivity growth in the period 2021–2023. These are the activities that have been an important driver of productivity growth and real convergence towards the more developed EU countries over the last ten years. In contrast, according to the data currently available, amid continued high activity in 2023, value added per employee increased sharply in construction. Productivity in knowledge-intensive services – ICT and professional, scientific and technical and administrative and support service activities – declined last year after strong growth in 2022, but this was due to increased employment, while value added actually increased slightly in 2023.

10. Unit labour costs

Unit labour cost, which measure the nominal wage/productivity ratio, rose sharply in 2023. They have been on an upward trend since 2019, with strong annual fluctuations that have characterised macroeconomic aggregates in the recent period. In 2022, the increase in cost pressures was mainly mitigated by the pass-through to prices (as measured by the value added deflator), which was no longer sufficient to mitigate the strong growth in nominal wages, or more precisely in compensation of employees per employee (+11.8%) last year. This exceeded nominal productivity growth by more than 2 p.p. (9.3%; 0.4% in real terms). As a result, real unit labour costs were also higher than during the global financial crisis, when the cost and therefore price competitiveness of the Slovenian economy deteriorated sharply, with profits also falling sharply during this period.

Growth in unit labour costs in 2023 was particularly high in market services and manufacturing, where the increases also diverged sharply from the EU average. Nominal wage growth in manufacturing (+12.3%) exceeded nominal productivity growth, measured in terms of value added per employee (10.0%), by more than 2 p.p. This also led to further widening of the gap with Slovenia’s trading partners and the EU average, where wage growth (6.6%) was closer to the nominal productivity growth (5.9%). Similarly, the gap in unit labour costs with the EU average widened further also in services in 2023, and even more so in traditional market services (trade, transport, and accommodation and food service activities), where unit labour costs in Slovenia rose by 7.1%. In addition to strong employment, knowledge-intensive services, which include information and communication, professional, scientific and technical, and administrative and support service activities, also recorded an increase in unit labour costs (4.7%). In construction, cost pressure in 2023 was mitigated by high productivity growth, i.e. value added per employee, which led to a decline in unit labour costs in 2023 despite an above-average increase in wages.

11. Export market share

After two years of contraction, Slovenia’s export market share in the global goods market increased by 6% in the first three quarters of 2023. In 2021 and 2022, it decreased by 2.4% and 4.8% respectively. The decline in 2021 was largely due to the product specialisation of Slovenian exports, i.e. modest foreign demand for some of Slovenia’s most important product groups (e.g. vehicles) and a significant increase in the value of international trade in raw materials (reinforced by price increases), which account for a relatively small share of Slovenian exports. The decline in market share in 2022 was largely due to a deterioration in competitiveness, as the rise in global commodity prices was accompanied by high growth in labour costs and domestic prices. The negative impact of the deterioration in competitiveness is also confirmed by quantitative data, which point to slower growth (2022) or a sharper decline (Q1–Q3 2023) in Slovenia’s real exports compared to quantitative trends in global demand. Despite the significant deterioration in cost and price competitiveness (see Section 1.2.1), which was comparable to that during the global financial crisis, the current data point to a smaller decline in export performance in 2022–2023 than in 2008–2012, measured in terms of both value and volume market share.

The EU market share grew by an average of 3% in the first three quarters of 2023, with significant differences in the main product groups. More detailed data on the export/import flows of EU Member States, to which Slovenia exports around three-quarters of all its goods exports, show that the main drivers of market share growth in 2023 were industrial machinery and equipment, whose market shares also increased during the health and energy crises. After two years of decline, the market share of the pharmaceutical industry, where only slightly more than half of exports are destined to the EU market, also increased on average in the first three quarters of 2023. In energy-intensive products, Slovenia’s market share in the EU market for chemical and non-metallic mineral products increased after a sharp decline in the previous year. However, the market shares of other energy-intensive products – paper and metals – declined in 2023. Among the main product groups, the market share on the EU market for electrical machinery and equipment and road vehicles continued to fall in 2023. The latter was already around one-third lower than before the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic.

12. Foreign direct investment

After increasing in the post-COVID-19 period (2021–2022), foreign direct investment (FDI) flows weakened in 2023 due to deteriorating financing conditions for international investment projects (driven by elevated inflation and interest rates). The value of inward FDI more than doubled in the last nine years (2015–2023), primarily owing to the inflow of equity capital, but also partly to debt instruments. Higher inward FDI was primarily due to the acceleration of the privatisation process and increased sales of equity stakes in Slovenian companies. There were also more expansions of the existing foreign-owned companies and new (greenfield) investment. EU Member States were the largest investors in Slovenia, with Slovenia’s main trading partners (Austria, Germany, Italy, Croatia and Switzerland) contributing about three-fifths of the total value of direct investment. The average implicit rate of return on FDI was 7.8%, the highest among the international investment components, reflecting foreign direct investors’ long-term interest. Outward FDI has been increasing since 2014 but at a relatively slow pace. In 2023, the stock of such investment was 48.2% higher than in 2010. Slovenian direct investors have the largest share of direct investment in the other countries of the former Yugoslavia. The declining share of goods exports to this region over the last eight years indicates that Slovenia is replacing part of its former exports with local production in these markets. The average implicit rate of return on foreign direct investment was 3.3%.

Slovenia is still one of the EU Member States with the lowest inward FDI-to-GDP ratio. Even though the inward FDI-to-GDP ratio had risen to 34.0% by 2023, it remains lower overall than in the other new EU Member States, although it recorded the highest growth among these countries in the period 2009–2022. In terms of its outward FDI-to-GDP ratio, Slovenia outperformed Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, Slovakia, Lithuania, Croatia and Latvia among the new EU Member States.

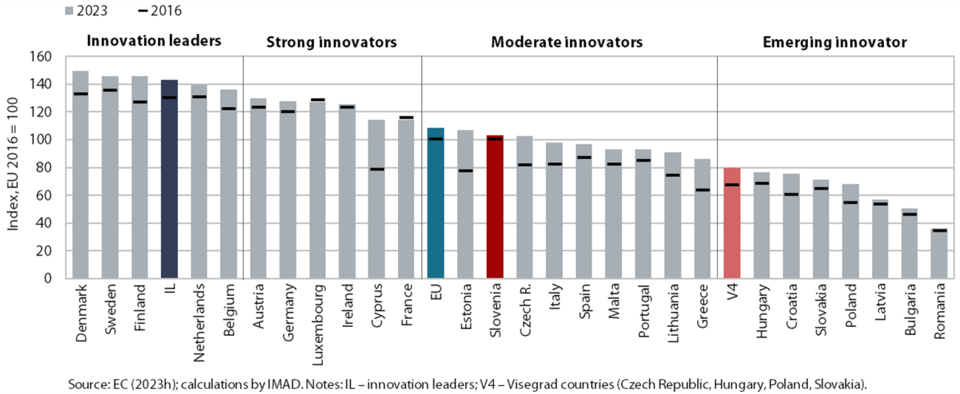

13. The European Innovation Index

According to the European Innovation Index (EII), Slovenia was again classified in the group of moderate innovators in 2023 and the significant gap to the average of innovation leaders remained unchanged. The EII measures the average research and innovation performance of EU Member States. Its value determines the classification of countries into four groups. The assessment of countries’ progress in the last EII measurement was based on the benchmark value of the EU average from 2016. Slovenia was classified as a moderate innovator for the fifth time in a row in 2023, outperforming the average for its group. Prior to 2018, Slovenia was classified higher (among strong innovators), with an EII value close to the EU average. The performance of the innovation system, as measured by the EII, deteriorated in the period 2016–2020, but the negative trend was broken in 2021, leading to Slovenia’s best result in relation to the EU average in 2023. Nevertheless, Slovenia’s overall progress in the period 2016–2023 was the fifth lowest in the EU. Slovenia therefore still lags far behind its SDS 2030 target of belonging to the group of innovation leaders (see Table).

Insufficient investment in R&D during the period 2016–2023 significantly weakened Slovenia’s EII ranking, while some indicators of innovation activity had the opposite effect. R&D investments were too low in both the public and business enterprise sectors, with the former already lagging well behind the EU average and both sectors lagging even further behind the innovation leaders. From 2019 onwards, public investment in R&D began to rise in some V4 countries (especially in Poland, while the Czech Republic constantly invested more than Slovenia). Business enterprise sector investment remains above that of the V4 and it is encouraging that it has also been slightly above the EU average for the past three years. Amongst them, spending on non-R&D innovation investment was significantly lower. The increased number of product and business process innovations introduced by SMEs in the 2018–2020 period has contributed to Slovenia performing better compared to the EU average and, for product innovation, also compared to the average of the innovation leaders.

14. R&D expenditure and the number of researchers

Expenditure on research and development (R&D) was increasing in nominal terms in 2018–2022, but relative to GDP it continues to lag behind the 2011–2015 period. In 2022, total R&D expenditure reached a record high in nominal terms (EUR 1,195 million), but in relative terms it stagnated for the third year in a row at around 2.1% of GDP, which is still slightly below the EU average and well below that of the innovation leaders. In 2022, public sector investment in R&D was also higher than ever before in nominal terms, but at 0.55% of GDP it was well below the 2011 level, before showing a decline with the consolidation of public finances. It was also relatively low in an international comparison (2021 EU: 0.71; IL excluding Denmark: 0.73; V4: 0.58% of GDP). After a decline in 2015–2017, business enterprise sector investment stagnated at around 1% of GDP (2021 EU: 1.30; IL excluding Denmark: 1.74; V4: 0.71% of GDP), while the business enterprise sector’s R&D performance showed a modest upward trend (as a share of GDP) over this period, though still remaining well below the 2013 peak.

Growth in the number of researchers in the business enterprise sector was halted in 2021 and their number has stagnated, albeit at a high level, in the last two years. In 2008–2020, the number of researchers (in full-time equivalents) increased primarily in the business enterprise sector, which is also the largest employer. The business enterprise sector employed 54.3% of all researchers on average in 2008–2022 and 57.9% in 2022. While the share of the Slovenian business enterprise sector has been above the EU average since 2011, it remains well below the average of the innovation leaders, which requires further attention against the background of a steady increase of the share in the V4 group (2022 EU: 56.7%; IL: 68.1%; V4: 54.4%). The public sector faced a decline in the number of researchers in 2011–2017, but this trend has been halted since 2018, which together with increased funding also for young researchers (ARRS, 2023) indicates an improvement in the trend. However, significant challenges persist regarding the improvement of career conditions (IMAD, 2023d).

15. Intellectual property

In 2023, Slovenia has significantly narrowed its gap with the EU average in the number of patent applications filed with the European Patent Office (EPO), although the gap remains large, as does the gap with the innovation leaders. According to provisional EPO data, Slovenian applicants filed 72 patent applications per million inhabitants in 2023, which is almost one-fifth more than the average in the period 2008–2023. However, the gap remains wide. In that period, the EU average was 2.4 times higher than in Slovenia and the average in the innovation leaders was 5.7 times higher. With regard to the level of patentability, as measured by the number of patent applications per million inhabitants, Slovenia ranked around 13th among EU Member States throughout the 2008–2023 period and took the leading position among the new EU Member States or was even ahead of some similarly developed countries (Spain and Portugal). In 2014–2023, Slovenian applicants filed about 20% of their applications in two technological fields (electrical machinery, apparatus and energy and organic fine chemistry) and about 10% in medical-related technologies (EPO, 2024).

Slovenia has made considerable progress in the area of trademarks since 2011, but a notable gap remains in the area of designs, despite some advancements seen in 2022–2023. In terms of EU trademark legal protection, the number of Slovenia’s applications per million inhabitants was mostly rising in 2008–2023, surpassing the EU average since 2019. However, concerning the number of registered Community designs, the gap with the EU average remained large throughout the 2008–2021 period. Although the situation has improved slightly in the last two years, this still indicates a lack of awareness of the importance of design in increasing value added. By filing a single application with the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), applicants can secure legal protection for either of the aforementioned intellectual property rights throughout the EU, leading to relatively lower costs and significantly faster legal protection procedures compared to patents, which affects their attractiveness for companies of all sizes and activities.

16. Corporate environmental responsibility

The ISO 14001 standard is still the most widespread environmental certification in Slovenia, followed by the Ecolabel, while the EMAS scheme is the least widespread. In an international comparison, Slovenia stands out the most for its high uptake of Ecolabels, ranking second among EU countries, behind only Austria. This is mainly due to accommodation establishments, which account for more than 70% of the Ecolabels awarded in Slovenia (compared to around 23% in the EU). The uptake of ISO 14001 certificates, the most widely used international standard for responsible environmental management, is also higher in Slovenia than the EU average, but Slovenia still lags behind most of the new Member States. The growth in the uptake of EMAS certificates is progressing at the slowest pace both in Slovenia and in the EU. Slovenia falls below the EU average in this regard but remains ahead of most of the new Member States.

Given the high number and variety of ecolabels, standardised rules are being adopted at the EU level in order to limit greenwashing. Within the EU internal market, there exist numerous eco-labels with varying management models (offering different levels of safety, control and transparency), with their numbers continuing to rise. This has an impact on consumers’ ability to make environmentally sustainable choices. In spring 2023, the European Commission therefore adopted a proposal for a directive on substantiation and communication of explicit environmental claims (the Green Claims Directive), in order to protect consumers from greenwashing, so that they can make more sustainable decisions. The proposal for a directive provides for common rules on environmental labels that go beyond existing legislation such as the EU Ecolabel Regulation, the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), Regulations on the organic farming label, energy efficiency labelling, and CE marking. The proposal for a directive is meant to act as a safety net for all sectors where environmental claims or labels are unregulated at the EU level (Rdeči karton zelenemu zavajanju, 2023; Green Claims Directive, 2023).

1. Share of the population with tertiary education

The share of adults (25–64 years) with tertiary education has been above the SDS target since 2020, although it remains considerably lower than in most economically developed EU countries. The share of adults with tertiary education has risen in the long term due to the high participation of young people in tertiary education and the transition of younger, on average better-educated people to higher age groups (a demographic effect). This growth was interrupted in 2022, but at 40.1% it remained above the EU average (34.3%). It was above the SDS 2030 target (35%) for the third year in a row, although it was lower than in most developed Northern and Western European countries (41–53%). The highest increase in the share over the period 2012–2022 was seen in the 35–44 age group, where it was also most significantly above the EU average in 2022. Despite the high participation of young people in tertiary education, the share in the 20–24 age group was below the EU average, which could be due to the longer time spent in education. Due to their higher participation in tertiary education, the share of women with tertiary educational attainment was higher than the share of men, and the difference between tertiary-educated nationals and those born abroad was larger than the EU average. The share of people with tertiary education was highest in the most developed Osrednjeslovenska region (48.9%), while it was the lowest in the Posavska region (30.5%).

Despite a decline, Slovenia’s share of employees with tertiary education was still above the EU average in 2022. The decline is attributed to the robust growth in the employment of people with low and upper secondary levels of education, which is linked to the increase in economic activity and employment in sectors that predominantly employ workers with low and upper secondary education (construction, manufacturing, and transportation and storage). In 2022, the share of employees with tertiary education was 46.6% (EU: 39.3%); in most private sector activities, it was lower than in the public sector.

2. Enrolment in upper secondary and tertiary education

The number of people enrolled in upper secondary education increased in the 2022/2023 academic year for the third year in a row. After declining for several years due to demographic reasons (smaller generations of young people), it has risen again in recent years with again a larger generation of young people and is now close to the level of ten years ago. The share of young people enrolled in general upper secondary schools fell in 2012–2022, while the share of those enrolled in vocational schools increased and has been above the EU average for several years. However, given the general labour shortage due to demographic reasons, the favourable economic developments and the high proportion of young people opting for tertiary education, employers are struggling to find workers with vocational education. According to demographic projections, the number of those enrolled in upper secondary education is likely to continue to rise in the future. In this context, it is crucial to equip future labour force with a range of skills to cope with the rapid transformations in the world of work brought about by the green and digital transition, technological change, a long-lived society, and other development trends.

The number of students enrolled in tertiary education mostly declined in 2012–2022 due to smaller generations of young people. In the 2022/2023 academic year, it was 19.9% lower than ten years ago. The only field where the number of students increased is health and welfare, where the share in total enrolments also increased the most and was above the EU average in 2021. The share of students enrolled in science and technology has been between 29% and 30% since the 2013/2014 academic year and was the sixth highest among EU Member States in 2021. However, against the backdrop of negative demographic trends, their number declined, which has a negative impact in terms of the future supply of human resources for the transition to a smart economy. The share of students enrolled in social sciences, which was also below the EU average in 2021, declined. Demographic forecasts indicate that the number of students will increase in the coming years and thus also the supply of graduates on the labour market. In the 2022/2023 academic year, the share of female students (57.7%) was similar to previous years. As far as the internationalisation of tertiary education is concerned, the proportion of foreign students has increased over the last ten years (to 10.6% in the 2022/2023 academic year) and was above the EU average according to the latest international data.

3. Tertiary education graduates

The number of tertiary education graduates decreased in 2022 due to the demographic trends and remained well below the 2012 peak. Due to the smaller generation of young people, the number of graduates mostly decreased over the last ten years and was 23.4% lower in 2022 than ten years ago. The most significant drop in the number of graduates was recorded in the social sciences, which account for a 28.2% share in the structure of graduates. The highest increase was seen in the share of health and welfare graduates, although it was still below the EU average in 2021 and is not sufficient to meet the needs of a long-lived society. From the perspective of the transition to a smart economy, the decrease in the number of graduates in science and technology (by 9.8% compared to 2012) has a negative impact, and although the share of these graduates is the sixth highest among EU Member States, it does not meet demand. The number of graduates in education, who are in high demand (see Section 2.1), was one of the lowest in ten years in 2022. In 2022, 59.3% of tertiary education graduates were women. Their share has not changed significantly over the years and is higher than the share of men in all fields of education, with the exception of science and technology.

In 2022, the number of new PhDs increased but was among the lowest in the last decade. It peaked in 2015 and 2016 but has mostly declined since 2017. These trends are related to a decrease in the number of enrolled doctoral students between the academic years 2012/2013 and 2015/2016 and on average longer time spent in education (in 2020 compared to 2012). The number of new PhDs per 1,000 inhabitants aged 25–34 (in 2021) was below the average in the EU and innovation leaders. In this comparison, the number of new PhDs in science and technology (per 1,000 inhabitants aged 25–34) was also lower. Such trends are unfavourable from the perspective of strengthening the country’s human resources in the fields of R&D and innovation. The number of those enrolled in doctoral studies in the 2022/2023 academic year was roughly the same as the previous year and was far from the 2011/2012 peak, which is unfavourable from the perspective of the future supply of professionals.

4. Performance in reading, mathematics and science (PISA)

In 2022, 15-year-olds in Slovenia performed worse in mathematics, science and reading compared to 2018. According to the PISA 2022 survey, the decline in the performance of 15-year-olds in Slovenia in mathematics, science and reading, which is an indirect indicator of the quality of the education system, was more pronounced compared to 2018 than the EU average. The deterioration was greatest in reading literacy (19th in the EU), while mathematical and scientific literacy are still above the EU average. In 2022, the SDS target (by 2030), which is to be ranked in the top quarter of EU Member States, was only achieved in science literacy, where Slovenia ranked a high fourth, behind only Estonia, Finland and Ireland. The share of 15-year-olds with low achievement (below proficiency level 2) increased across all literacy types between 2018 and 2022. One of the targets of the Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training is that the share of 15-year-olds with low achievement (below proficiency level 2) in reading, mathematics and science should be less than 15% by 2030 on the respective literacy scale. Slovenia no longer meets this target in any of the literacy types. In 2022, the figures were 26.1% in reading, 24.6% in mathematics and 17.8% in science (OECD, 2023).

Inequalities in the learning achievements of 15-year-olds increased between 2018 and 2022. In 2022, girls achieved better results than boys in reading and science and the same as boys in mathematics. Fifteen-year-olds with the highest socio-economic status performed better than their peers with the lowest socio-economic status in all three literacy types; the gap between the two groups was narrower than the EU average but widened between 2018 and 2022. Fifteen-year-olds with a migration background performed worse in reading than their native peers, the difference between them being larger than on average in the EU.

5. Education expenditure

In 2022, public expenditure on education (as a % of GDP) fell and, similar to private expenditure, was comparable to the EU average. Public expenditure as a share of GDP declined between 2012 and 2017. In the first few years, the decline mainly resulted from austerity measures after the global financial crisis, changes in social legislation and demographic reasons. In 2018–2021, it rose again slightly, with annual fluctuations, and then declined in 2022, falling 0.6 p.p. short of the 2010 peak, with the gap being widest in upper secondary and tertiary education. In 2020 (latest international data), public expenditure on education was comparable to the EU average and the average of the 22 EU Member States that are also members of the OECD but much lower than in the economically developed countries (Sweden, Denmark, Belgium and Finland). Only expenditure on basic education was above the EU average, while expenditure on tertiary and upper secondary education lagged most significantly behind. Private expenditure on education amounted to 0.64% of GDP in 2022 and was higher than in 2021; according to data for 2020, it was about the same as the EU-22 average (0.56% of GDP).

Although expenditure (both public and private) per participant in education mostly increased in the last decade, it remained low by international comparison. In 2020, the last year for which internationally comparable data are available, expenditure on education per participant (in USD PPS) was below the EU-22 average at all levels of education. For several years, the largest gap has been recorded at the upper secondary school level (the gap was wider in vocational and technical education than in general upper secondary education), where the participation of young people in education is high, while public and private expenditures are low.

6. Participation in lifelong learning

Participation of adults (aged 25–64) in lifelong learning increased for the second year in a row in 2022, surpassing the SDS target for the first time. Participation has mostly declined since 2010, most sharply with the outbreak of COVID-19 epidemic in 2020. In 2021, it rose sharply, largely due to the increase in webinars, the increased availability of publicly funded training and the wide availability of free training; the data were also impacted by a change in methodology. In 2022, participation in lifelong learning increased even further and, at 22.3%, for the first time exceeded the SRS 2030 target (19%), which is also the target of the Resolution on the national programme of adult education in the Republic of Slovenia 2022–2030. Participation in Slovenia was well above the EU average (11.9%) and behind only Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland among all EU Member States. Participation in lifelong learning has increased in all age and education groups but is still the lowest among people with a low level of education and older people (55–64 years). The highest participation rate was recorded in the Osrednjeslovenska region, the lowest in the Koroška region. In 2022, participation increased in all regions except the Koroška and Primorsko-Notranjska regions.

Broken down by activity status, the largest increase in participation in lifelong learning in 2022 was recorded among the unemployed, while the highest participation was still seen among persons in employment. The participation of persons in employment and the unemployed in lifelong learning was significantly above the EU average, while the participation of inactive persons was slightly above the EU average and also saw the smallest increase compared to 2020. Differences in participation also exist among persons in employment. Participation is higher on average in activities with a higher share of tertiary-educated people. It is highest in finance and insurance and education and lowest in construction, accommodation and food service activities, and administrative and support service activities.

7. Attendance at cultural events

In 2022, the attendance at cultural events increased, although it was still well below the 2019, i.e. pre-epidemic, levels and below the SDS target. The average attendance per inhabitant was highest in 2012, owing to the many events hosted by Maribor, the city that held the European Capital of Culture title that year. In the remaining years it was almost half lower (around 5–6 visits per inhabitant). In 2020, the average attendance at cultural events per inhabitant fell sharply due to COVID-19 containment measures. In the following years, when containment measures were less strict or were lifted, it gradually increased again but remained below the levels already reached and the SDS target. The highest number of visitors in 2022 was again recorded in houses of culture and cultural centres, but despite the higher number of events than before the epidemic, the number of visitors has not returned to previous levels. The largest increase in 2022 was recorded in visits to film screenings, with Slovenian film screenings recording a strong increase and accounting for 17.1% of all screenings, the highest figure in ten years. Of all the types of cultural institutions, only attendance at musical institutions in 2022 was above the level of the pre-epidemic period.

Cultural institutions carry out many activities enriching the cultural offer; in 2022, the number of these activities increased after falling temporarily, though it was still lower than before the epidemic. The number of events held by institutions with stage activity fluctuated between 2016 and 2019, then dropped significantly in 2020 due to the epidemic, before rising in 2022 for the second year in a row, when it was only 2.3% lower than in 2019. By type of activity, the highest attendance was recorded for film screenings, musical events, and events showing dramatic and other theatre works, while the lowest attendance was recorded for ballet events (see Section 2.2). In 2022, institutions with stage activity performed the highest number of new works since 2016, 8.2% being co-productions with foreign co-producers and 56.2% with Slovenian co-producers. They organised fewer festivals than in 2021 but many more festival events. Museums and galleries organised fewer exhibitions in 2022 compared to 2021 (due to fewer temporary exhibitions). Film production, measured by the number of feature films produced, increased in 2022 after declining sharply in the previous two years.

8. Share of cultural events held abroad

In 2022, the share of cultural events held abroad increased and came close to the pre-epidemic levels. Touring is an indirect indicator of the quality of cultural production in the country and signifies recognition of good work. The share of cultural events held abroad reached the SDS target in 2017–2019 but declined sharply in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 epidemic. In 2021 and 2022, when containment measures were gradually lifted, it rose again and, according to the latest data, stood at 3.6%, once again exceeding the SDS 2030 target (3.5%). A stronger increase can be seen in the share of museum events, which came close to the 2016 peak, and a slight increase was also recorded in the share of the performing arts. In the structure of cultural events held abroad, the share of those held in other EU Member States was 82.8% in 2022, which indicates the geographical attachment of Slovenian culture to this area.

Although the number of visiting events from abroad increased in 2021, it remained lower than before the epidemic, especially in stage activity. Visiting events from abroad enrich the offer of cultural events in the country and show the extent of cooperation with cultural institutions from abroad. After a sharp decline in visiting events from abroad due to the epidemic and the containment measures, the number of visiting events from abroad increased in 2022 for the second year in a row, while the share of visiting cultural events from abroad fell (to 2.8%) due to the lower share of stage activity. Three-quarters of visiting events from abroad came from EU Member States – the largest share to date.

1. Healthy life years

Healthy life expectancy at birth in Slovenia exceeds the EU average. The more years that a person on average spends healthy, the less pressure there is on social protection systems due to early retirement and demand for health and long-term care services. A SURS (2019) analysis showed that the very low value of this indicator in Slovenia in recent years was mainly related to inadequate translation and the method of surveying, which was already partially corrected in 2019 and fully corrected in 2020. The indicator improved slightly further in 2021 over 2020. On average, Slovenians can expect 65.4 years of healthy life or life free from any limitation (EU: 64.2 years), falling short of the SDS target only in the number of healthy life years for men. Healthy life expectancy at age 65 improved slightly, to 10.7 years (EU: 9.7 years). Moreover, since 2020, Slovenia no longer lags behind the EU in terms of the share of healthy life years in relation to life expectancy. In 2021, healthy life years represented 81.2% of the total life expectancy in Slovenia (EU: 79.6%).

In 2021, healthy life expectancy at birth was the longest for men in the Primorsko-Notranjska region and for women in the Gorenjska region. Healthy life expectancy varies considerably among regions. The biggest difference is between men at birth. Men born in 2021 in the Primorsko-Notranjska region can expect to live 14.3 more years free from any limitation (67.3 years or 85.2% of life expectancy) than men in the Zasavska region, women in the Gorenjska region (74 years or 86.6% of life expectancy) 9.5 more than women in the Posavska region. In 2020, healthy life expectancy at birth increased the most for women in the Primorsko-Notranjska region (by 6.5 years) and for men in the Podravska region (by 2 years). Women can expect more healthy life years than men in all regions with the exception of the Posavska region, with the largest gap in the Zasavska region (11.5 years).

2. Life satisfaction

In 2023, life satisfaction peaked in Slovenia and was well above the EU average, with 93% of satisfied respondents. It was 2 p.p. higher than in 2022, 1 p.p. higher than before the COVID-19 epidemic and 4 p.p. higher than before the global financial crisis. On average in the EU, overall life satisfaction remained at the same level as before the pandemic. In recent years, life satisfaction has risen in the Member States that had low satisfaction rates before the epidemic, such as Bulgaria and Greece, and fallen slightly in the Member States with above-average satisfaction rates. In 2019–2023 (last survey in the year), the largest increase in the share of those satisfied was seen in Poland (by 9 p.p.). In autumn 2023, Slovenia ranked 8th in the EU, for the first time behind Poland and ahead of Germany, where satisfaction has fallen by 5 p.p. points in the last four years.

The shares of those citing problems of rising prices and energy supply decreased significantly at the end of 2023 compared to the beginning of the year at all three levels: personal, national and the EU. According to the latest survey (October–November 2023), the main concerns of Slovenian respondents were no longer energy supply and rising prices, but the war in Ukraine, immigration and terrorism (higher than the EU average). Among the most important concerns at the national level, the proportion of Slovenian respondents citing the climate crisis and immigration increased compared to the previous survey (by 10 p.p. and 20 p.p. respectively), while the share of those citing health, pensions and energy supply fell, although the decline in Slovenia was less pronounced than the EU average. The percentage of those citing inflation and the cost of living, the financial situation of the household, and the economic situation in the country as the main concerns at the personal level was still high in Slovenia, although it was lower than in previous surveys and lower than the EU average. Satisfaction with the financial situation of the household and personal job satisfaction in Slovenia were at an all-time high in autumn 2023. Compared to the survey conducted in mid-2023, satisfaction with personal job situation increased by 4 p.p. in autumn 2023, and satisfaction with the financial situation of the household by 1 p.p. In our estimation, this was due to the high employment rate and government measures to mitigate the impact of rising (energy) prices on the financial situation of the population.

3. The Gender Equality Index

In the last three years, the Gender Equality Index (GEI) for Slovenia was slightly below the EU average. Until 2017, the country had made faster progress in terms of gender equality than the majority of other EU Member States. Since then, however, progress has stalled, mainly due to a lower score in the area of power (lower political participation of women). After a period of decline in previous years, the GEI rose to an unprecedented high of 69.4 points in 2023. Nevertheless, Slovenia still ranks 12th among EU Member States. Progress in the areas of knowledge and power were the main drivers for the increase in the overall score. In order to meet the SDS 2030 target (> 78), Slovenia should improve its GEI score by more than eight points by 2030.

Since 2010, Slovenia has achieved the highest scores in the areas of health and money, while gender inequalities have been the most pronounced in the areas of knowledge and power. Men more often than women consider that they are in good or very good health, but health-related risk behaviours are more prevalent among men. In 2021, women were more likely to report that their needs for medical and dental examinations were not met than men. In the field of knowledge, the proportion of people participating in lifelong learning and the proportion of persons with tertiary education have increased, but the unequal distribution of women and men in different fields of study remains a challenge. Gender segregation is thus present in various labour market sectors. In Slovenia, the gender gap in employment rates is relatively low and the gender pay gap is below the EU average (see Section 3.2). Women’s representation in politics declined in 2018–2021, followed by an increase in 2022. According to the latest data for 2023, the share of women in the Slovenian Parliament was 37.8% (EU: 33%) and the share of women ministers was 33.3% (EU: 33.4%) (EIGE, 2024). The proportion of women in leadership positions in the largest listed companies remains relatively low and below the EU average. In 2022, slightly more women (26%, EU: 34%) than men (24%, EU: 25%) were responsible for the daily care of others. Greater inequalities were seen in unpaid housework, which was carried out daily by 69% of women (EU: 63%) and only 29% of men (EU: 36%).

4. Life expectancy

In 2022, life expectancy at birth in Slovenia nearly returned to pre-epidemic levels. Overall, at 81.3 years, it was a good three months below the 2019 figure (the gap was greater at the EU level). Life expectancy at the age of 65 in 2022 (19.8 years) was only slightly more than three months lower than in 2019 (similar to the EU). Life expectancy at the age of 65 in 2022 was 17.8 years for men and 21.5 years for women. Excess mortality was lower in 2022 and 2023 (11.2% and 6.2% respectively) than in the first two years of the epidemic (2020: 18.8%, 2021: 15%). Due to higher mortality with COVID-19 among the elderly, the average age at death was still higher (78.7 years) than before the epidemic, while the premature mortality rate was lower (2022: 14.5%). In the decade prior to the epidemic, gains in life expectancy had been slowing down in many OECD countries. The main causes that have made it difficult for countries to maintain the previous progress in reducing deaths from circulatory diseases are slowing improvements in reducing death rates from heart disease and stroke, rising levels of obesity and diabetes, as well as population ageing (OECD, 2023d). When it comes to future trends in life expectancy, the number of indirect deaths related to the unavailability of preventive and emergency health services and psychosocial support during the epidemic remains unknown (OECD and EU, 2020).

In 2022, life expectancy at the regional level was higher than before the epidemic, especially among men, and premature mortality decreased in most regions. Women in the Obalno-kraška region (84.7 years) and men in the Osrednjeslovenska region (79.6 years) had the longest life expectancy at birth. The difference between the two extreme regions was 2.7 years in men and 3.4 years in women. Compared to 2021 and 2019, life expectancy increased for men in particular, especially in the Podravska and Koroška regions (by around 1.6 years) and for women in the Pomurska region (by 1 year). Premature mortality decreased in most regions compared to 2021, with the largest decrease compared to other regions in the Zasavska and Posavska regions, where, as in Jugovzhodna Slovenija, the decrease was highest among men (23%). Among women, it was also highest in the Zasavska and Posavska regions, but only about half as high as among men. It was lowest in the Goriška region (5.9%).

5. Unmet needs for healthcare

In 2023, 3.8% of the Slovenian population reported unmet needs for healthcare, which is lower than in 2021 but still significantly higher than before the COVID-19 epidemic and higher than the EU average. The main reason cited for the extremely high unmet needs in 2021 were the containment measures adopted in 2020, which led to doctor’s appointments being postponed and waiting times being extended to 2021. In 2022, the epidemic situation improved, which was also reflected in lower unmet needs, compared to a slight increase in the EU on average. In 2023, unmet needs remained at roughly the same level as in 2022.

The main reason cited for unmet needs in Slovenia were long waiting times, while the percentage of respondents citing financial reasons was small. This is related to a broad healthcare benefits basket and very low out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare (see Indicator 3.8). In practice, access to many services is limited by long waiting times, which has been the main reason for unmet needs in Slovenia for many years. The gap in unmet needs between the first and fifth income quintiles, which is relatively small compared to other EU countries, has narrowed slightly compared to 2021. One reason for this is the public healthcare system, which is accessible in terms of affordability. However, both the financially weak and the better off have to contend with long waiting times.

The unmet needs for dental examination in Slovenia are also linked to waiting times. In 2022, unmet needs for dental examination decreased significantly but remained above the EU average. In 2023, 4.0% of the population reported having such unmet needs; the main reason was long waiting times for dentists in the public health network.

6. Avoidable mortality

Avoidable mortality, which declined in 2011–2019, increased in 2020 as a result of the epidemic, though less sharply than the EU average. The rate of avoidable mortality consists of (i) preventable mortality that can be avoided through effective public health and prevention interventions at the primary level and (ii) treatable mortality (avoidable by healthcare interventions). Avoidable mortality declined in 2011–2020 (to 268 deaths per 100,000 people, which is below the EU average) by almost twice as much as the EU average (by 64 deaths; EU: 38 deaths). In 2020, it deteriorated sharply due to the epidemic (by 23 deaths; EU: by 28 deaths). In addition to the direct deaths from COVID-19, the deterioration is also associated with indirect consequences caused by interruptions in preventive and curative healthcare.

Preventable mortality again decreased at a rate similar to the EU average in 2020 and remained above the EU average. In 2020, the number of deaths per 100,000 people that could have been avoided in Slovenia through effective public health and prevention interventions increased by 26 (the same as the EU average). Most preventable deaths are related to a high prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles, as the main causes of deaths are lung cancer (smoking) and alcohol-related diseases. The decrease in the death rate before the epidemic can be attributed to the strengthening of primary prevention interventions focusing on smoking, alcohol consumption, nutrition, physical activity, screening programmes and counselling (OECD/EOHSP, 2021).

Treatable mortality also decreased in 2020, which indicates relatively effective healthcare from the aspect of treatment. In 2020, fewer people died from causes that could have been avoided through timely and effective healthcare interventions compared to 2019 (including through screening programmes and treatment) (the number increased in the EU on average). The indicator points to effective healthcare in terms of treatment, particularly with regard to the relatively lower expenditure on health than in countries that reach comparable results. The main causes of death were heart disease and colorectal cancer, followed by strokes and breast cancer.

7. Overweight and obesity

The share of overweight or obese adults in Slovenia increased to 56.6% in 2019, surpassing the EU average. According to the EHIS survey, in 2019 (latest available data), the majority of EU Member States reported lower rates of overweight or obesity among individuals with higher education levels, while rates were higher among those with lower education levels and among women (Eurostat, 2024). Over the period analysed, the proportion of overweight or obese adults in Slovenia and the EU average rose by 1.6 p.p., while the proportion fell significantly among men with a low level of education, who were the largest risk group before the last survey. A high share of overweight or obese people can be associated with poor eating habits and excessive alcohol consumption. In 2020, the average annual alcohol consumption per capita was 9.8 litres in Slovenia, which is in line with the EU average, but 23% of adults reported heavy episodic drinking (EU: 19%) (OECD, 2022d). Overweight and obesity are important risk factors for the development of chronic conditions and premature mortality. Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of mortality in Slovenia and in most developed countries. Obesity can, moreover, have not only medical but also socio-economic consequences (social exclusion, lower income, higher unemployment, more working days lost and early retirement).

According to the SHARE survey, which is conducted among people over the age of 50, around 70% of people in Slovenia were overweight in the three periods observed from 2013 to 2020, which is significantly above the EU average. The most recent SHARE survey, conducted partly before the epidemic and partly in the summer of 2020, found almost the same proportion of overweight (71%) among those aged 50 and above as the previous two surveys (46% overweight and 25% obese people). Compared to Slovenia, the average share of overweight people in the EU-27 included in the last SHARE survey declined, to 63% (of whom 40% were overweight and 23% obese). Switzerland had the lowest proportion of overweight or obese people (51%), while Malta had the highest (83%). In Slovenia, the proportion of overweight or obese individuals in all observation periods was highest among those with upper secondary education, while the proportion was lowest among those with a high level of education. The gap by educational attainment has widened since 2013 among those above 50 years of age, due on the one hand to a decline in the share among those with a high level of education and on the other to an increase in the share among those with a low level of education.

8. Health expenditure

After stagnating in relation to GDP for several years, health expenditure has increased since the outbreak of the epidemic. Slovenia entered the epidemic with a severely underfunded and understaffed health system. Total health expenditure remained at around 8.5% of GDP between 2009 and 2019, although demand has risen rapidly due to the ageing population, the introduction of new health technologies and the population’s increasing expectations in the area of healthcare. The problems have resulted in a rapid increase in waiting times and unmet needs for medical examinations, which were exacerbated by the epidemic (see Indicator 3.5). In 2020–2022, the high expenditure related to the COVID-19 containment measures was largely financed from the state budget, meaning that state and municipal budget expenditure as a share of current health expenditure increased from 4.2% in 2019 (EUR 173 million) to as much as 12.7% in 2021 (EUR 626 million), followed by, according to preliminary estimates, a decline to 9.2% in 2022 (EUR 482 million). The share of total current public expenditure in total expenditure increased from 72.8% in 2019 to 74.3% in 2022.

From 1 January 2024, a new mandatory healthcare contribution was introduced to compensate for the funds lost due to the abolition of complementary health insurance. Complementary health insurance (CHI) was to cover all co-payments for healthcare until the end of 2023. In 2022, the CHI contribution to total healthcare expenditure amounted to 12.1% or EUR 632.7 million, according to the preliminary estimates by SURS. From 1 January 2024, a new mandatory healthcare contribution of EUR 35 was introduced, which will be indexed to the growth in the average gross wage in 2024 for the first time in March 2025 (see Section 3.1, Box 5). This will lead to an increase in the proportion of public health expenditure to around 86% in 2024, one of the highest shares in the EU.

9. Expenditure on long-term care

In 2021, the share of public expenditure on long-term care (LTC) increased significantly for the third year in a row, but as a share of GDP it was still below the EU average. Already in 2019, the share of public expenditure on LTC increased sharply in the structure broken down by financing schemes, mainly due to the adoption of the Personal Assistance Act (ZOA, 2017), which significantly increased public financing for LTC at home. In 2020 and 2021, public expenditure on LTC further increased, partly due to the employment of additional staff in nursing homes and wage supplements related to the epidemic and partly to rising expenditure on personal assistance: the number of personal assistants and recipients of the communication allowance increased significantly (from around 1,000 at the beginning of 2019 to almost 6,000 at the end of 2023). International comparison shows that public expenditure on LTC in 2021 (latest data available) amounted to 1.8% of GDP on average in the EU, while in Slovenia it was 1.1%. There are large differences between countries, with the highest expenditure in 2021, between 2% and 4% of GDP, recorded by the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Finland and France. In addition to the different levels of economic development, these differences also reflect differences in LTC systems, demographic factors and life patterns, particularly regarding the role of family and informal care. In Slovenia, a new LTC act came into force in 2024, providing additional public funding and accelerating the development of LTC at home (see Box 6).

The share of the health component of LTC expenditure in the structure of health expenditure is only 70% of the EU average. Despite the very rapid increase in 2019–2021 (by 12% in real terms), expenditure on the health component of LTC is still much lower in terms of EUR PPP per capita than the EU average (2021: 70% of the simple average and only 50% of the weighted EU average) and 3 to 4 times lower compared to more developed countries. These countries have increased their public funding for LTC at home in the last decade and for institutional LTC in 2020 and 2021 in connection with the epidemic.

10. Employment rate